As lignin oxidizes, it breaks down into acids that eat away at paper’s cellulose and turn the pages yellow.

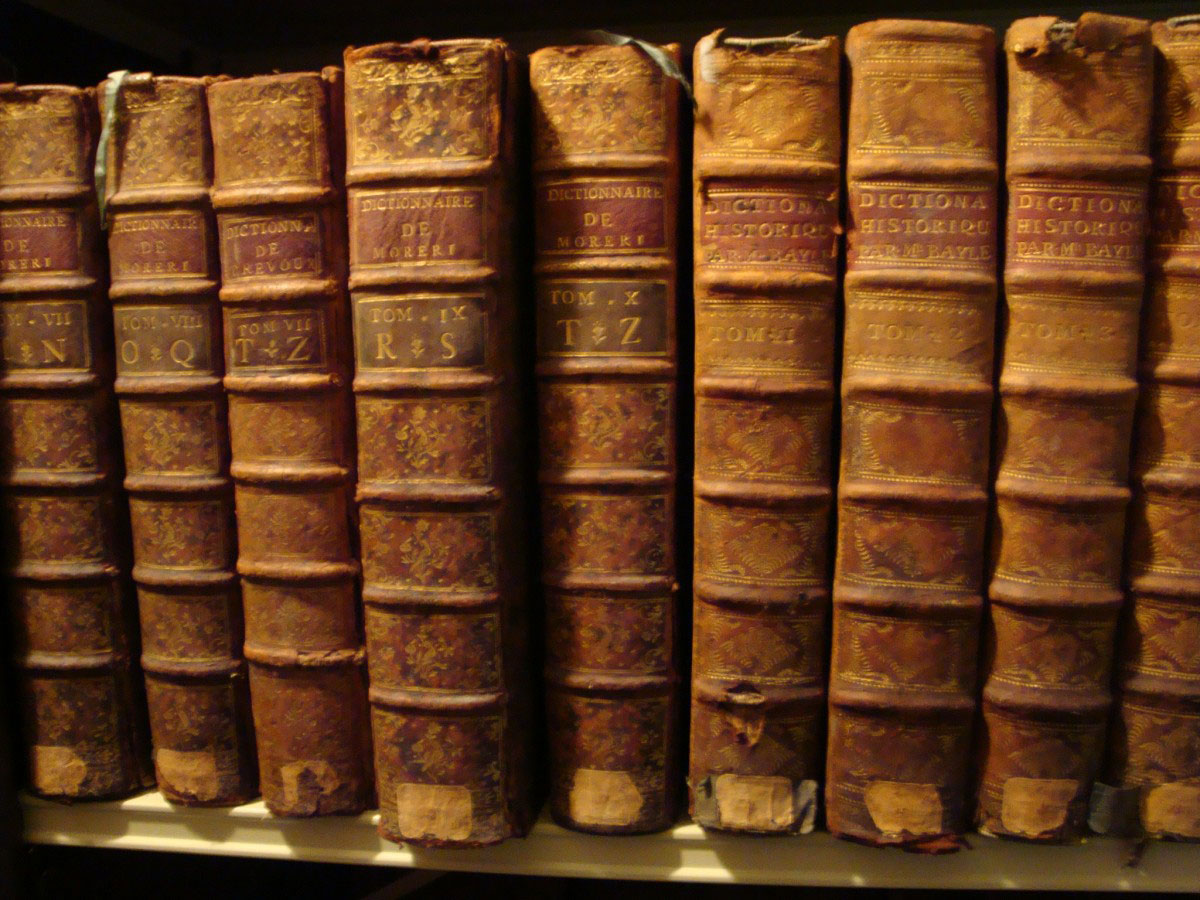

What early bookmakers didn’t realize was a lesson only learned over time: lignin is strong during a plant’s life, but it’s prone to wild and destructive decay after death. In trees, lignin binds cellulose fibers together and gives wood its extra backbone-which would seem like a desirable quality for bookbinding. Wood-pulp paper has heavy lignin content unless you extract the lignin deliberately finer-quality papers tend to contain less lignin than newspaper. This produced paper that was less durable than paper made of cotton or linen, but more plentiful and therefore cheaper. The 1840s saw the invention of a process to manufacture paper from wood pulp fibers. Cellulose is largely stable in paper over the years unlike its cousin lignin, another plant polymer frequently present in paper. These plants contain a high percentage of cellulose, a kind of polymer that gives plants stiffness. Before 1845, paper in books was manufactured from cotton and linen rags. But the materials from which books are made have shifted over the centuries-and those shifts, in turn, have influenced how different generations of books smell. Books are largely paper, and paper is largely plants. The smell of old books stems from their slow chemical decomposition. Writ large like this, old books smell like a constructed forest: ancient and druidical, exhaling to make their own atmosphere, a forgotten primordial home. But just as often you encounter this smell as a solid wall in a used bookstore or library. You can smell a single old book, riffle through its pages rapidly and let your nose bask in the scented breeze. This is an intimate smell that’s not necessarily miniature. Undisturbed dust, with its suggestion of perfect stillness and the happy dilation of hours spent reading.

The litany of things book-smell resembles suggests elements of peaceful civilization: Well-rubbed wooden furniture. The disembodied words of writers, whether dead or otherwise absent, find body in these volumes. Ghosts, like smells, are composed of particles, a levitating cloud forming a slightly denser shape than the surrounding air. Readers who find this smell intoxicating are ruefully aware of how insane, how flatly contradictory of convenience, loving this smell can be.įrom an old book filters up a whiff of dissolution and conjuring. Imagine all the cardboard boxes necessary to crate up a roomful of books, the slow trundle of cargo to a new destination, the books aging along with their owner from move to move. In smelling old books, you can smell actual geographic distances, too. And sometimes books fail to jump high enough. Sometimes a great book sticks the landing, very often they don’t. You sense time travel, of course, but also the soaring aeronautics of ideas. Inside its dry and musty hull, the smell of old books contains great distances.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)